I will be using a digital literary approach to Adams and Bradbury’s materialist view of objects as sites of gender negotiation in my Breton lai corpus (Adams and Bradbury 1-3). I used the Voyant Collocate tool to look at words to the right and left of my target object terms to identify the gendered context for the items.

Object Study: An Elcel-lent Statistical Process

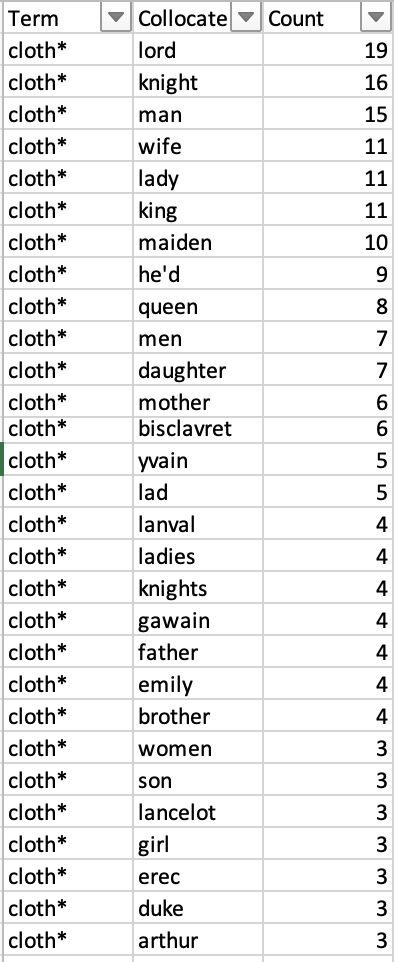

A Collocate is produced for cloth*.

From there, I created an Excel spreadsheet with the information.

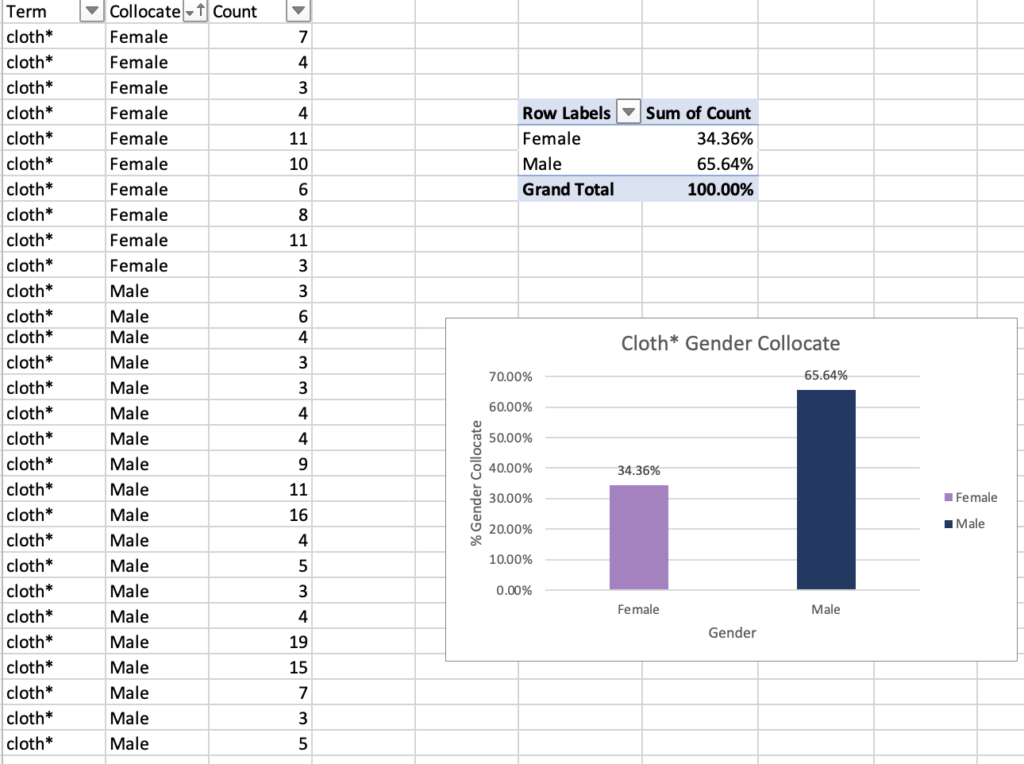

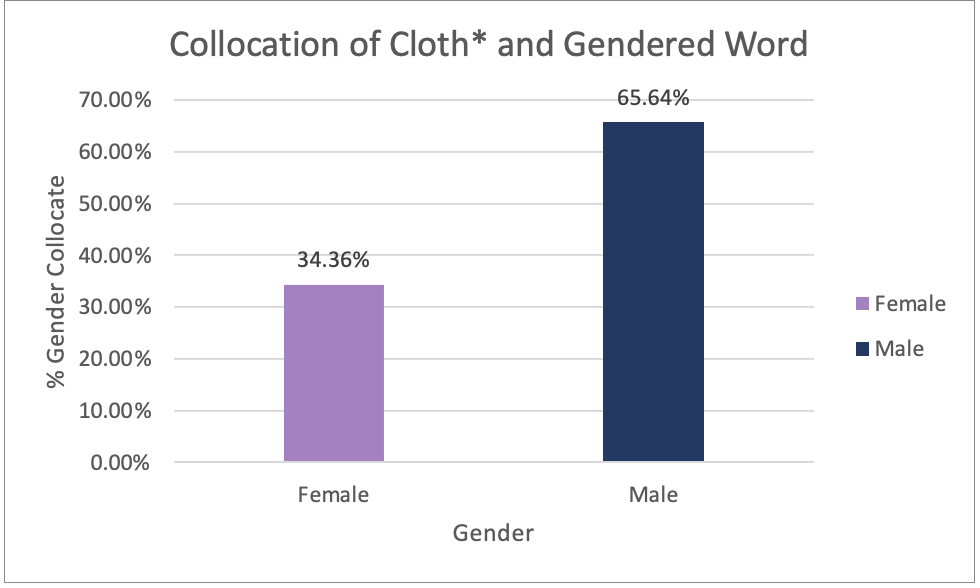

I then deleted all collocate words that did not denote gender before changing the individual collocates to either Male or Female. As an example, in Cloth* Male terms were lord, knight, knights, man, men, lad, king, duke, he’d, father, brother, son, Bisclavret, Yvain, Lanval, Gawain, Erec, Lancelot, and Arthur whereas Female terms were women, wife, daughter, mother, lady, ladies, maiden, queen, Emily, and girl.

A PivotTable was then created with the sum of the count of collocates as a percentage of the grand total.

Feminine Object Use

I will proceed with applying Adams and Bradbury’s approach to “take a material view of objects, showing them as sites of gender negotiation and resistance: buildings, books, pictures extend women’s bodies, opening spaces normally closed and making public bodies often kept private” (Adams and Bradbury 3). As previously noted, the color, quality, or cleanliness of clothes appears in the corpus. Clothing can be a site of gender negotiation as it represents the public displays of wealth and position.

More importantly, clothing often displays female labor. In Henrietta Leyser’s Medieval Women: a Social History of Women in England, she notes the history of all classes of women spinning and weaving gives “spinsters” and “wives” their respective names with “weaving batons are found regularly in women’s graves” in Anglo-Saxon England (14). However, it is important to note the prominence of female weavers did not always extend to female financial success. As Leyser notes, women were spinsters “carding and combing wool were also…jobs primarily done by women; weaving, by contrast, was in the hands of men. Looms were costly and they took up space few women had at their disposal…Female textile workers seldom figure among the more affluent section of the working population” (161-162). Nevertheless, the women creating, mending, and maintaining clothing was vital. Following this approach, I imagined cloth*—a search term containing cloth, cloths, clothing—would be near female nouns and pronouns.

Although I expected cloth* to be associated with women more often than men in the corpus, the results of the collocate show the opposite. Although cloth could be spun, mended, and cleaned by women, it is likely cloth in the text is worn and used by men more often. In Breton lais, the use of the object takes precedence over the care. Further, the number of male characters in the text may impact the corpus overall.

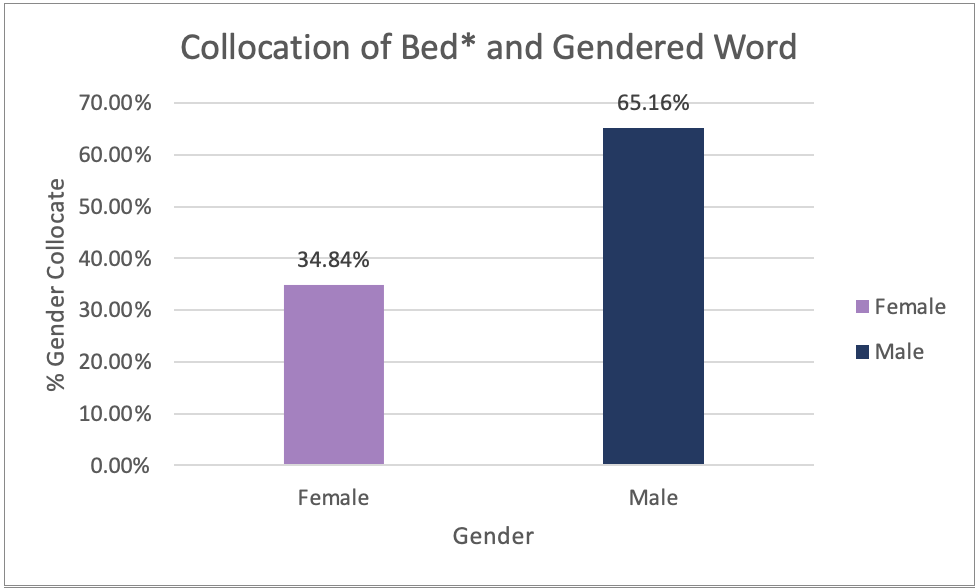

Looking further into other potentially female coded objects, I turned to the bed* gender collocate. Similarly, the graph also favored male collocates. The bed is a private space of rest, one often associated with female characters in the text, as women’s private bedrooms provide spaces for romantic trysts with errant knights in towers, like in Marie de France’s Yonec or in Sir Gawain and The Green Knight. Although these scenes are prominent, they often also include male characters.

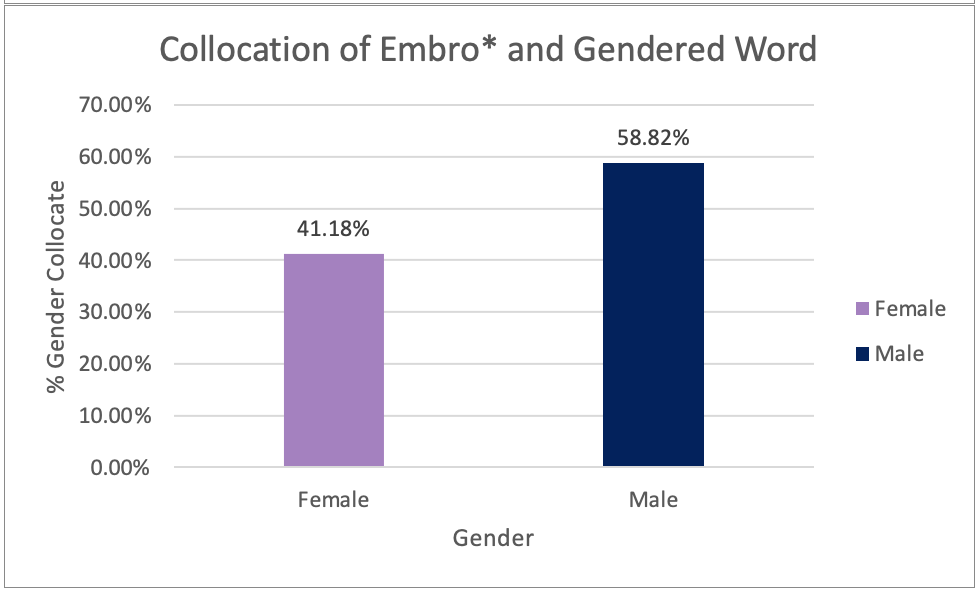

I then considered words with less frequency in the text might more frequently be collocated with female markers, so I turned to the embro* search—containing both embroidered and embroidery. Looking into the context of embroidery, I found several embroidered items in all four texts from birds and butterflies to golden bands.

Liza Picard looks to examine the daily lives of medieval English people in the fourteenth century through Chaucer’s characters in Chaucer’s People: Everyday Lives in Medieval England. She notes “Satins were often embroidered with gold or silver thread, or patterned with small motifs in gold leaf” (260). She further explains Chinese silk arrived in Europe in the eleventh century and by the fourteenth-century silk was also being woven in Italy (Picard 260). Additionally, she notes “London embroiderers were famous for their embroidered silk” (Picard 260). This combination of practices likely accounts for the number of embroidered silk items across the texts as a sign of wealth and luxury.

However, embroidery also fails to be mostly associated with women. The texts primarily describe the final products of embroidery like worn embroidered clothes or hanging embroidered tapestries. Embroidering is typically omitted from the corpus. While the texts use products traditionally associated with women’s work, at least in these instances, those products are not primarily associated with women in the corpus. Further examination of additional objects may reveal differences between texts and gender use.

Masculine Object Use

Now, for objects with male connotations, I decided to look at battle objects like shields, swords, and lances using this same method. Battle objects, traditionally used and worn by men in the corpus still can be associated with women, perhaps to varying degrees between items, due to the role of Courtly Love in the corpus.

In Rethinking Chivalry and Courtly Love, Jennifer G. Wollock studies the history of chivalry, with Chivalric literature encompassing both true and false tales of knights, and tales of Courtly Love, including tales where knights have a longing relationship with a lady outside of marriage (37, 119). I am specifically looking at Courtly Love as portrayed by knights both promoting female sovereignty and performing “love longing, a form of suffering that was imagined to transform the lover’s personality for the better” (37-41). Although this describes the earliest depiction of Courtly Love, as seen in the 1100s, the tradition also appears in the latter half of my corpus.

Cathy Hume examines the history of love and marriage in Chaucer’s work in late medieval England in Chaucer and the Cultures of Love and Marriage (4). She argues in late medieval English and French aristocracy, participation in Courtly Love expresses a culture “of flirtatious conversation and compliments, male-female friendship, tolerance of love affairs outside marriage, and conventions of secrecy and male service to women” (145). Courtly Love appears as a way of performing acts for or in service to women in the corpus.

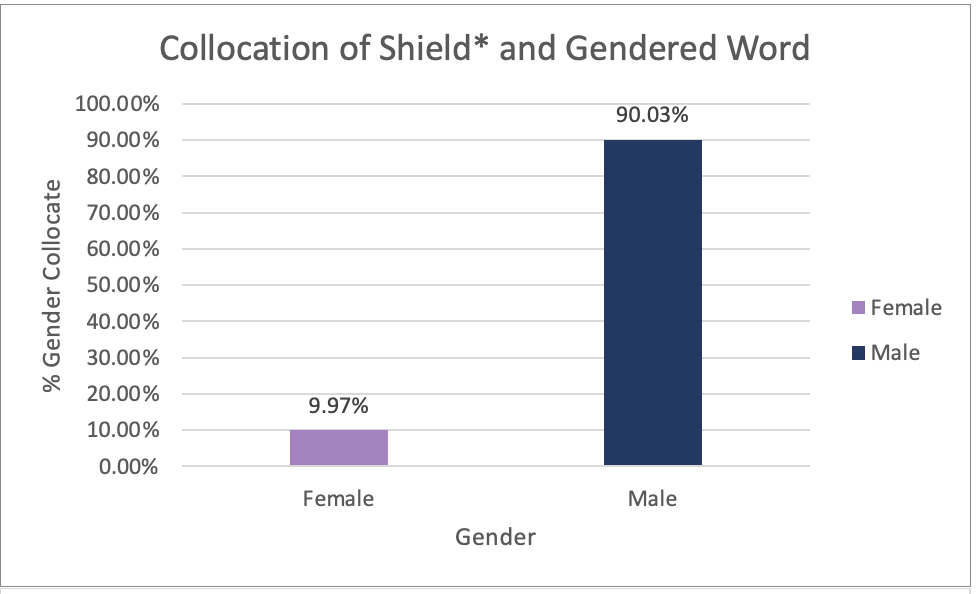

Looking at battle objects with recognition of Courtly Love in the Breton lai allows us to look at traditionally male objects as cities of female gender negotiation. For the shield, I produced the below collocate graph.

Although I was expecting majority male connotations, the degree to which shields were associated with masculine characters was surprising with female collocates making up only 9.97% of the data. This relatively small percentage indicates men hold and possess shields in the corpus. Shields pledged to women or women handing shields over to men before battle as an act of Courtly Love may account for this percentage.

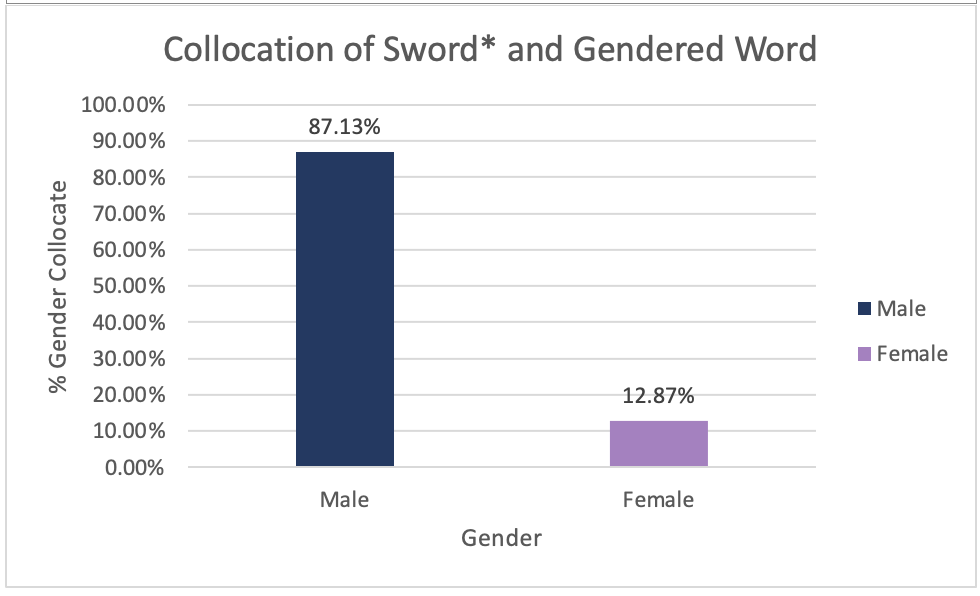

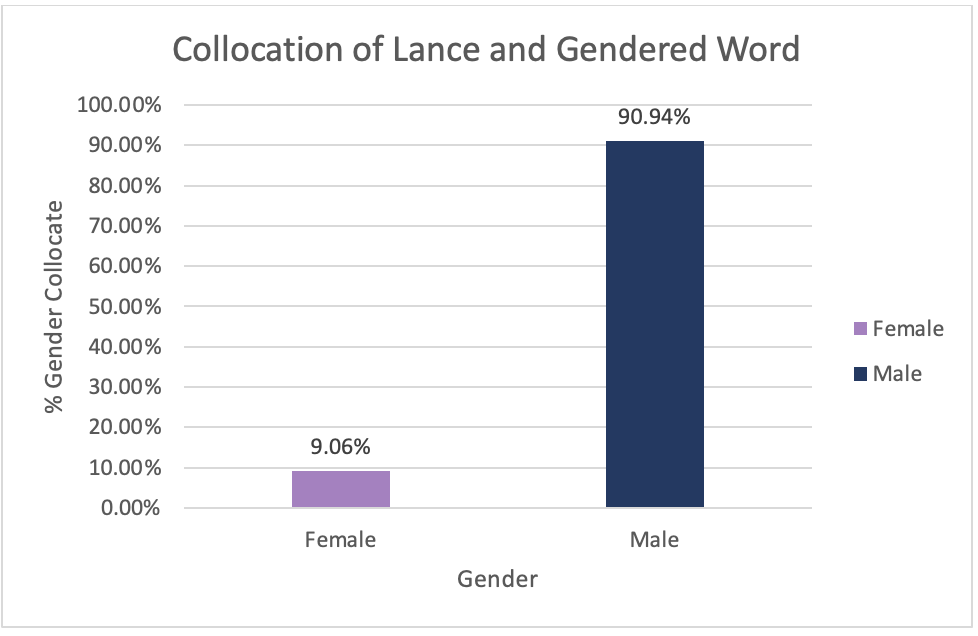

I expect the graphs for swords and lances to be similar, with a wide gender disparity.

Interestingly, there is a greater percentage of female collocates making 12.87% of the data. Although this is far less than words like bed* it is higher than the shield. There may be an association between men pledging their swords to women or using swords to protect women in the text, as an indication of Courtly Love increasing the percentage of female collocates.

When I moved on to lances, I expected to find swords and lances have similar data. Interestingly, Picard notes the arrêt de la cuirasse, an advance in jousting armor design in the 1380s, allowed jousters to use both of their shoulders and their chest to improve their aim (245). Although one would expect the historical advance to lead to an increase in lances in the texts from the 1300s (Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer), lances mostly appear in an earlier text, The Arthurian Romances by Chrétien de Troyes, with 191 of the 199 hits. Nevertheless, I found the following data an interesting indication Courtly Love impacts the gendered-object-use in the text.

Interestingly, the lance graph shows a percentage difference more similar to the shield data with the female collocate percentage at 9.09% of the data, showing lances are more likely used in battle apart from female figures.

In Short: My Views on Gendered Objects

After examining the gendered connotations of object words in the text, I found that while some objects are more associated with women, no object examined here is associated with more women than men. Battle objects in the texts tend to be associated with men and they are handled or wielded by women a small percentage of the time. The data indicates Courtly Love operates across the corpus, impacting traditional sites of female gender negotiation (Cloth*, Bed* and Embro*) as well as male sites on gender negotiation (Shield*, Sword*, and Lance*)

By focusing on objects as the site of gendered tension where Courtly Love can be seen in the percentage difference between gendered object collocates, we can examine the role of the devotion to ladies in Courtly Love. Following this lens, the male collocate percentages may come from a focus on women by knights. In the Breton lai, women become the focus of male attention or love-longing in the text, motivating the plots. The actions are ultimately performed by knights or men, changing the gendered-object-use. Although men are more likely to be using objects in general, and more specifically, battle objects, the female percentages that appear account for the role of Courtly Love in battle and the corpus as a whole.